You Already Know Frank Lloyd Wright — Now See Houses by 3 of His Illustrious Female Colleagues

It’s easy to think of architects as a singularity, but the truth is, architects hardly work alone. Architecture is very much a team effort of an entire studio, even if only the top dog gets the credit in the history books. When it comes to preeminent 20th-century architect Frank Lloyd Wright, this is almost certainly the case — we think of the majority of his oeuvre to behisworks alone, when the reality is that dozens of architects beneath him contributed greatly to many of those projects. And, in a fascinating twist, more than 100 of the architects he worked with were women.

For more content like this follow

In the early 1900s, architecture was almost exclusively the domain of men (and it remains a male-dominated field today). But Wright changed the narrative; his first hire at his Oak Park, Chicago, studio was a woman, Marion Mahony Griffin, in 1895. He continued working with women not only at his private firm, but also at his Taliesin architecture schools in Spring Green, Wisconsin, and Scottsdale, Arizona, which he founded in 1932. Some 20 to 25 percent of applicants to the Taliesin Fellowship, as the program was called, were women, and many of them were accepted. AtTaliesin, Wright was said to treat men and women equally. Outside of their studies, fellows — no matter their genders — were expected to complete chores, from working in the kitchens and performing manual labor outdoors.

“他愿意雇佣大多数历史学家属性women to the fact that he wanted to surround himself with the most talented designers and architects, regardless of gender,” says Rebecca Riggs, an architectural historian with design firm Stantec. “Wright demanded perfection and expected excellence from all of his employees, but he also reserved a certain amount of respect for women within the professional setting, likely due in large part to being raised by his mother and his two aunts. He was surrounded by strong women from an early age and carried that trend into his professional life.”

Despite holding that respect for women professionally, he wasn’t fond of giving them — or the men he worked with, for that matter — credit for their work. “Everything that came out of his studio came out under his name, even if he didn’t wholly create the design himself,” says Riggs. “He was known for holding design contests and keeping the winning designs for himself and using them as his own.”

So in honor of Women’s History Month, here are the stories of three of Wright’s colleagues who were women, who deserve their turns in the spotlight.

Marion Mahony Griffin

Born in Chicago in 1871, Griffin was the second woman to graduate from the architecture program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the first woman to become a licensed architect in Illinois. Wright hired her in 1895. She was instrumental in helping Wright develop his signature Prairie Style, using her skills as a draftsman to bring to life his visions through dazzling watercolor drawings. It was Griffin’s brush that created the illustrations most commonly attributed to Wright himself — the ones that would set a new standard for how architectural projects were presented in perpetuity. But she was also a brilliant architect in her own right.

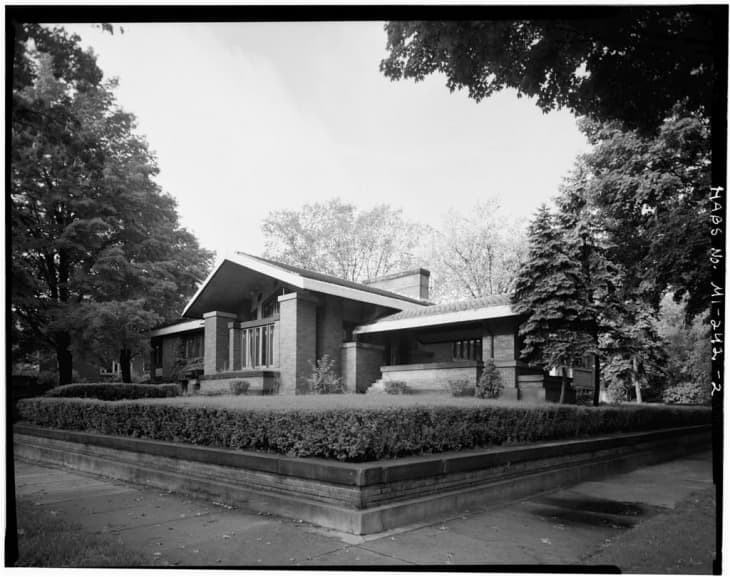

When Wright ran away to Europe with a lover — his personal relationships with women were far more tempestuous than his professional ones — Griffin became the design lead of his studio in his absence, alongside Walter Burley Griffin, whom she would later wed. While the Griffins were the creative force behind such projects as theAmberg House in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Wright received the credit.

The Griffins would eventually move to Australia as the designers of the urban plan for Canberra, the country’s new capital. Though Marion and Walter were equals, her husband received most of the credit. But Marion’s colleague Barry Byrne described her as “the most talented member of Frank Lloyd Wright’s staff,” adding that “[he doubted] that the studio, then or later, produced anyone superior.” She outlived her husband by 24 years, passing away in 1961.

Lois Gottlieb

When she was a senior at Stanford University in 1947, Lois Gottlieb discovered Frank Lloyd Wright through a visit to hisHanna-Honeycomb Houseon the school’s campus. Her experience was transcendental; Gottlieb immediately applied for Wright’s Taliesin Fellowship, to which she was accepted in 1948. After two years studying under the master, she continued her education at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design.

In 1951, Gottlieb partnered with her Taliesin classmate Jane Duncombe to found the firm Duncombe-Davidson (using Gottlieb’s maiden name) in Sausalito, California. The two split a few years later to pursue independent careers — unlike many of Wright’s fellows who were women, Gottlieb was able to make a name for herself as an independent architect.

She designed her magnum opus,The Gottlieb House in Fairfax Station, Virginia, for her son in the mid-1990s, in the twilight of her career. The structure is riddled with Wrightian principles and details, from its panoramic windows that open to nature to geometric wood light fixtures. Gottlieb incorporated similar details intoher condo in San Francisco, too, despite its distance from the outdoors. After a storied career, Gottlieb died in 2018 at the age of 94.

Eleanore佩特森工作室内由手工制作完成

At first, Eleanore Pettersen didn’t choose architecture as her career path. When she enrolled at New York’s prestigious Cooper Union for Advancement of Science and Art in 1937, she intended to study painting. But after taking a drafting class, she changed course.

The decision would prove to be a wise one. Pettersen graduated from Cooper Union with an Architecture certificate in 1941, then immediately began her Taliesin fellowship. After two years, she struck out on her own, first in Tennessee, then in her native New Jersey. There, Pettersen was the first woman to become a licensed architect and the first woman to open her own studio in the state. (She eventually became licensed in a total of seven states.) Her most famous commission was theAlford-Nixon House in Saddle River, New Jersey,originally designed for businessman John Alford, but then purchased by former president Richard Nixon after his departure from office.

“I think if I hadn’t gone to Wright’s, I wouldn’t be sitting here. There’s no question about it,” said Pettersen in a filmed interview featured ina short documentaryabout Wright’s distinguished women colleagues. (It was produced by the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation, an invaluable organization dedicated to promoting the legacy of female architects.)

Pettersen’s legacy as a pioneering female architect continued throughout her career. She eventually became the first woman president of the New Jersey Board of Architects, the first woman president of the New Jersey chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), and the first woman president of the New Jersey Society of Architects, among other accolades. Pettersen passed away in 2003 at her home in New Jersey.